False Confession Day can be seen as a time to celebrate pranksters who confess to things they haven’t done to appall their friends and amuse themselves.

But there is a darker side to the day, as well.

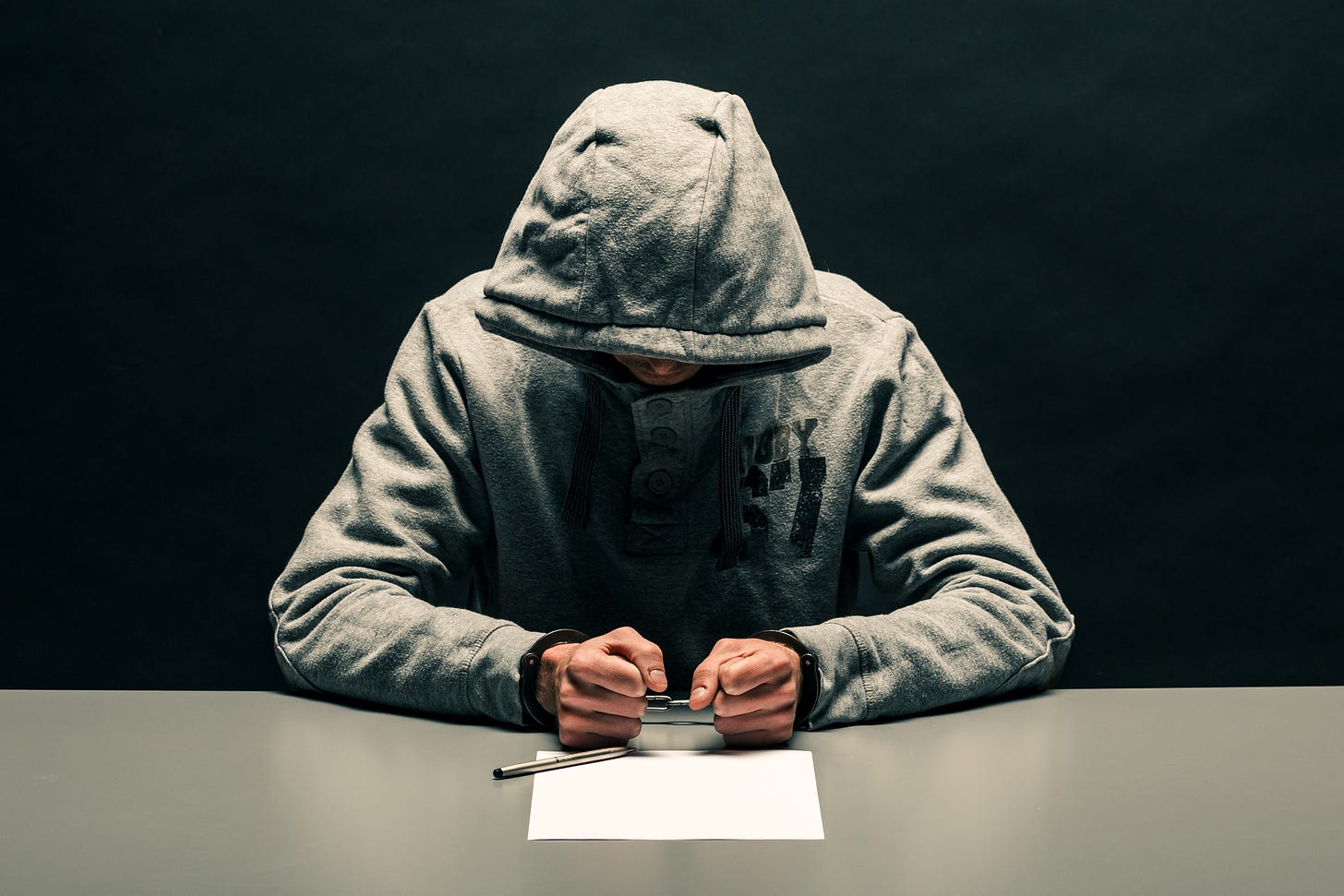

False confessions to crimes are disturbingly common for serious felonies such as murder that can lead to life imprisonment and even execution in the US. According to the Innocence Project, of 258 people they have exonerated by using DNA evidence, 25% involved a false confession. One of the most notorious instances of false confession was the case of the Central Park Five. In that 1989 case, a woman named Trisha Meili was brutally assaulted and raped on her evening jog in Central Park. Five teens were arrested, interrogated without their parents’ presence, and all confessed, and later recanted their confessions. They were nevertheless convicted, and all served time in prison. It was more than a decade later that the actual assailant was identified, and the Central Park Five were officially exonerated.

The tactics used by police to get the false confessions are common, although more recently some have been discredited, specifically because they often produce unreliable results. Particularly the use of intimidation of suspects who are youths, or who are disabled, or developmentally delayed, or vulnerable because of mental illness.

But studies have shown that anyone can be vulnerable to interrogation tactics such as prolonged interviews; the Innocence Project found that on average people who falsely confessed to crimes did so only after 16 hours of interrogation during which they denied involvement. Another technique that can elicit false confessions from even those who have no extraordinary vulnerabilities, is when police lie to suspects and tell them the evidence against them is irrefutable, which it is legal for them to do, or that there are witnesses who will testify to their guilt, even when there are no such witnesses.

The Innocence Project among other organizations that advocate for wrongly convicted people have been pushing for change in the ways that police conduct their interrogations, and with some success. But, possibly because confessing to something you didn’t do is so counterintuitive to most people, who have never been in such a situation, change has been slow.